Ché Rhodes Glass Art, 1900s Jellico Mining Co. Scrip Coin, 1968 Louisville Rebellion “Hurricane’s Eye” Relic, and More

As members of the Frazier’s exhibitions and collections team, I and my colleagues have spent the last several weeks working weekends and long hours on the museum’s next exhibition, The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall.

I’m happy to say The Commonwealth was nearly complete for the member and VIP preview last Thursday. We have just a few minor tweaks and additions to get it ready for everyone to see on the June 1 public opening. (That date, by the way, is no accident: it marks 230 years since Kentucky became the fifteenth state of the union!)

I am so proud of many things in The Commonwealth, but I am especially proud of the portion of the exhibition that has been designed in partnership with the (Un)Known Project. With their support, we were able to commission a glass installation from local artist Ché Rhodes. Ché currently has work on display at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in a show titled This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World. Ché’s piece from this show has recently been added to the permanent collection at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It is a privilege to work with such a renowned artist on such an important project.

From left, Ché Rhodes and Amanda Briede at Amanda’s senior thesis show at the University of Louisville, 2009. Credit: Amanda Briede.

Despite his accolades, I am most excited to work with Ché because he was my mentor while I majored in glass blowing at the University of Louisville. Only this time, the tables have turned, and I am the one giving deadlines and writing assignments.

One of many things Ché taught me at U of L is the power and importance of materials. These lessons have been important for my work as a curator, and it is why I knew glass would be the best material to use in our space dedicated to the (Un)Known Project. In the following video, Ché talks about why he used glass—specifically, clear glass—for this installation.

That video is part of a longer interview with Ché I conducted at the Frazier and the Cressman Center for Visual Arts, U of L’s glass blowing studio—which I helped build during my second semester of glass classes. Among other topics, Ché and I discussed my time at U of L, his mentor Stephen Rolfe Powell, and his experiences as a Black man in the art glass world. He even let me help with one of his glass pieces, marking my first time working with glass in about eight years.

You can see the full interview here.

I hope you will take time to come see Ché’s piece in The Commonwealth when it officially opens June 1!

Amanda Briede

Curator

Frazier History Museum

This Week in the Museum

Countdown to The Commonwealth: Jellico Coal Mining Co. Scrip Coin, 1903–30

Logo for The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

Each week leading up to the opening of the Frazier History Museum’s next permanent exhibition The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall, manager of collection impact Hayley Rankin will highlight an object or objects to be included in the exhibition.

Opening to the public June 1, 2022, The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall will tell the story of Kentucky’s rich history, including, among other topics, its native peoples, the Civil War, and the early nineteenth century, when cities such as Louisville gained prominence due to their important locations along the Ohio River. It will expand viewers’ personal connection to history by pairing historic figures like Henry Clay, emancipationist Cassius Clay, and Abraham Lincoln with diverse narratives from lesser-known figures in Kentucky history.

In partnership with artist Ché Rhodes and the (Un)Known Project, led by artist-run nonprofit IDEAS xLab, the exhibition will include a space for visitors to reflect on the stories, both known and unknown, of the enslaved that lived in Kentucky. This interactive exhibition is designed to engage visitors of all ages and will feature objects related to Kentucky’s diverse history as a border state on the banks of the Ohio, including the clock face from the top of the Town Clock Church in New Albany, Indiana, an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and the Bloedner Monument, the oldest surviving memorial to the Civil War.

The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.—Amanda Briede, Curator

Front side of ten-cent scrip coin for use in the Jellico Coal Mining Company store, 1903–30. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

Back side of ten-cent scrip coin for use in the Jellico Coal Mining Company store, 1903–30. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

In Whitley County, Kentucky, situated near the southeastern border of Kentucky and Tennessee, is Mountain Ash, a small, unincorporated community that originated as a coal town for the Jellico Coal Mining Company. Like many coal companies of the early 1900s, the Jellico Mining Co. issued scrip coins to miners for purchasing goods in the Jellico company store. Scrip coins are private currency that often come in the form of metal tokens. The use of scrip coins, such as this ten-cent coin, kept miners and their families dependent upon the provision of the coal companies so they would remain in coal towns and continue to work there.

The Jellico Coal Mining Company, named for the Jellico Mountains in Tennessee, began mining around 1883 after the discovery of the Jellico coal seam drew several mining companies to the area. Jellico coal was considered a high-ranking “steam and grate” coal, so numerous coal towns populated Whitley County by 1910 to increase production.

Although the number of coal towns and miners has decreased over 200 years of commercial mining, due in part to changing technologies and environmental concerns, Kentucky still remains one of the top producers of coal for the United States today.

To learn more about the history of coal mining in Kentucky, visit The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall.

Hayley Rankin

Manager of Collection Impact

Museum Store: Kentucky Pillows and More

Kentucky pillows sold in the Frazier’s Museum Store, May 17, 2022. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

We stand united for Kentucky and we have the pillows and shirts (and more) to let everyone know which state we love. Find fun Kentucky merch in our online store.

History of 1968 Louisville Rebellion “Hurricane’s Eye” 1032 S. 28th St.

It’s a trial that played out in Louisville in the late 1960s after an uprising in the Parkland neighborhood: a trial that ended with the Black Six being acquitted, but not before it took a toll on them, and their lives. The case is still teaching us lessons today. Perhaps you read about the Black Six in Courier Journal reporter Bailey Loosemore’s May 16 article. The CJ is one of our partners along with Lean Into Louisville for our program tomorrow night. Key players will join us for the discussion, including members of the Black Six and their families. Several members of the Delahanty family will be in the audience as tribute to Bob Delahanty, one of the lawyers who defended the Black Six. There is still time for you to sign up, too. My colleague Simon Meiners conducted some research on the history of the location where the uprising started. Keep reading to learn more.—Rachel Platt, Director of Community Engagement

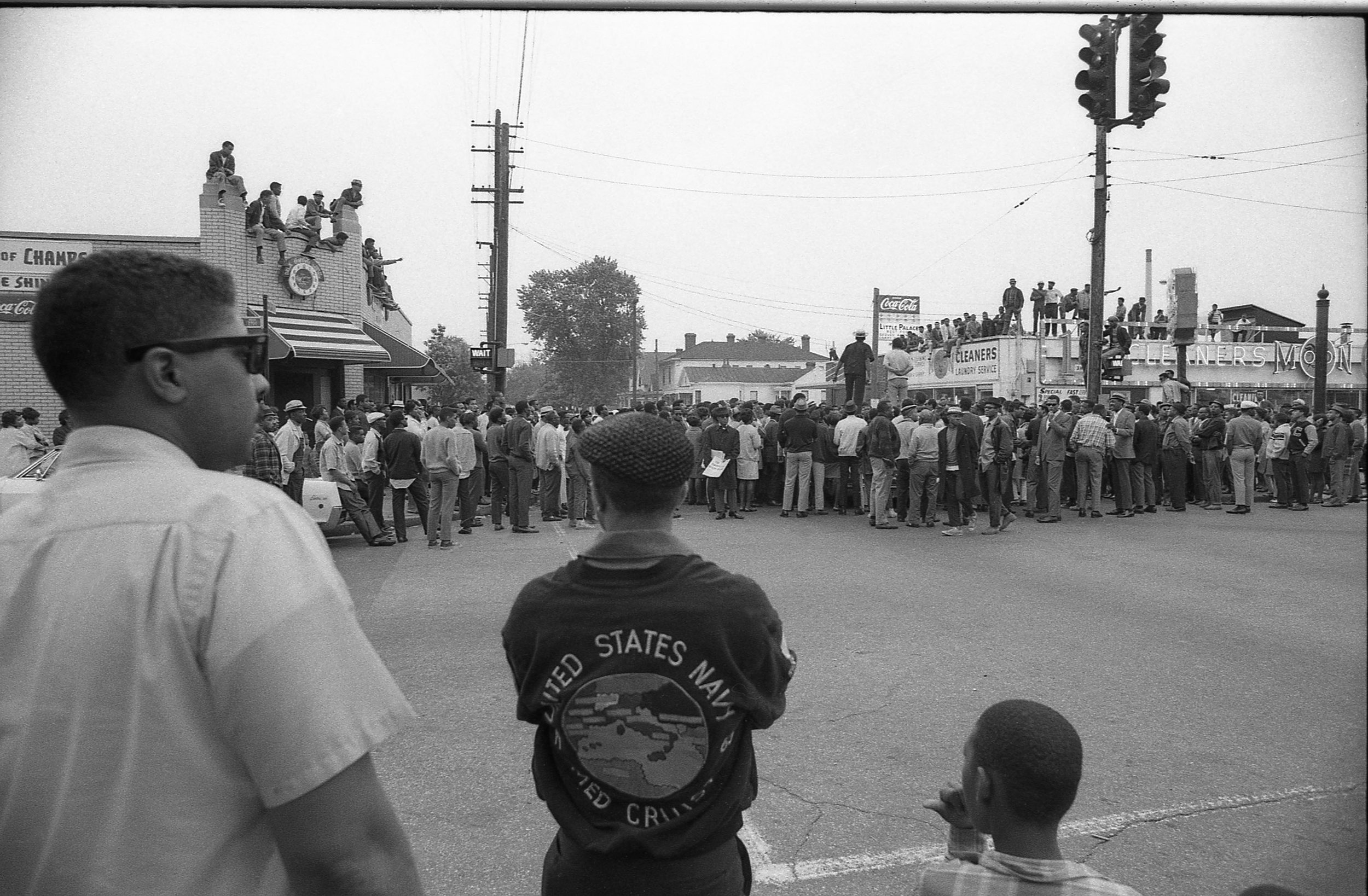

On May 27, 1968, a riot erupted at 1032 South Twenty-eighth Street in the Parkland neighborhood of the West End of Louisville. During the course of the three-day uprising, two youths were killed, ten people were hurt, and 472 were arrested.

The events that preceded the riot, the three days of upheaval, the deployment of 1,450 National Guardsmen, and the subsequent prosecution of six individuals—the “Black Six”—on trumped-up conspiracy charges are all topics to be discussed in tomorrow night’s “Black Six” program at the Frazier.

After the uprising, many business owners either declined to rebuild their business or decided to relocate to another area. One example of that phenomenon is 1032 South Twenty-eighth Street, then the site of Moon Cleaners and Laundry.

A meeting takes place outside Moon Cleaners and Laundry, located at 1032 South Twenty-eighth Street, at the southwest corner of Twenty-eighth and Greenwood, in Parkland, May 27, 1968. In the distance, two men standing on a car address the crowd: Sam Hawkins, head of the Black Unity League of Kentucky, wearing a dark shirt, and James Cortez. Both would later be charged, along with the other four members of the “Black Six.” Credit: Robert Steinau, Courier Journal.

Previously a hardware store in the 1930s and a tavern in the late ‘40s, the building at 1032 had by 1958 become a Moon Cleaners and Laundry, one of the chain’s thirty-plus locations in the city of Louisville. A front page article in the May 29, 1968, issue of the Courier Journal titled “The Hurricane’s Eye: 28th and Greenwood” cites Moon Cleaners and adjacent businesses as the epicenter of the uprising:

The intersection of 28th and Greenwood is the hangout, the place the guys go after school or work to shoot pool and drink a few beers. There is always a crowd at the intersection. So, it was almost natural that if rioting were to break out in Louisville it would be at a place like this. And it did.

The House of Champs’ poolroom is on one corner. “That’s where the black brothers go when there’s nothing else happening,” a 16-year-old Shawnee High School junior explained as he leaned against the front of Habeebs Dispensary which is across the street from the poolroom. Catty-corner from the poolroom is the Metro Lounge. Across the street from it, Moon Cleaners and the Little Palace Restaurant.

“When urban renewal moved everything out of the Walnut area this became one of the only gathering places for eight or ten blocks,” said Ken Clay, an anti-poverty worker who runs The Corner of Jazz, a Negro art shop next to the pool hall. “There’s just nowhere else to go at night for a bite to eat or a beer.”

It was the normal evening crowd, plus several hundred other Negroes attracted by the anticipation of seeing Stokely Carmichael speak, that gathered here at a rally Monday night. Carmichael didn’t make it to the rally. A man who said he was a Carmichael aide said “honkeys” (white people) kept his plane from landing, a report that proved to be untrue.

Image republished on page D1 of the May 28, 1978, issue of the Courier Journal. Credit: Robert Steinau, Courier Journal.

In 1978, Courier Journal city editor Ben Johnson wrote a thorough reflection of the events he witnessed the day of the uprising. Johnson, who was seventeen at the time, is pictured in Robert Steinau’s famous photograph of Hawkins and Cortez standing on a car addressing the crowd gathered at Moon Cleaners: He is situated to the left of the man standing on the corner of the roof of the building. According to Johnson, here’s what happened when Cortez told the crowd Carmichael wouldn’t be coming:

Minutes later, a brick and some light bulbs were tossed from the roof of the Moon Cleaners building where I had watched the rally with scores of others. The exploding bulbs sounded like gunshots. Nearby officers must have thought likewise. A police car quickly screeched into the intersection of 28th and Greenwood. A brick slammed into the face of a white officer as he jumped out. And all hell broke loose.

By October 1968, police had charged at least six individuals in connection with the uprising—albeit on conspiracy charges. After charges against three of the six—Cortez, Hawkins, and Sims—were dismissed, the three were charged with conspiracy to destroy private property owned by several area businesses: a taxi company, a refining company, a pawn shop, and Moon Cleaners.

In response, the West End Community Council urged a boycott of the taxi firm and Moon Cleaners, as the owners of those two businesses had been listed as witnesses in the indictment.

By 1975, the cleaners had not shuttered its Twenty-eighth Street location; however, the ownership had changed hands. It was now operating as Senator’s Laundromat, a coin laundry owned by state Sen. Georgia Davis Powers. Regardless, the intersection had buckled under the forces of disinvestment.

Johnson’s 1978 article continues:

The intersection is quiet now, as is much of the “riot corridor.” Most of the stores that were looted are boarded up. What used to be the bustling Parkland shopping center has the aura of a ghost town. There is a hardware store here, a barber shop there, the office for the Advancement of Colored People just across the street.

In the 1990s and 2000s, a nonprofit named Rivers of Living Water Tabernacle operated out of the adjacent address, 1034 South Twenty-eighth Street. But by the 2010s, the building was vacant, and sometime between 2015 and 2018, it was razed.

Detail of Steinau’s photograph, May 27, 1968. Credit: Robert Steinau, Courier Journal.

Southwest corner of Twenty-eighth and Greenwood, May 22, 2022. Credit: Simon Meiners.

Sign at the southwest corner of Twenty-eighth and Greenwood, May 22, 2022. Faded letters on the sign read “RIVERS OF LIVING WATER TABERNACLE,” the name of a nonprofit that operated at 1034 South Twenty-eighth Street in the early 2000s. Credit: Simon Meiners.

Today, if you visit what the CJ called the “hurricane’s eye”—the southwest corner of Twenty-eighth and Greenwood—you’ll find just one physical relic of the 1968 Louisville Rebellion: a large white sign with chipped paint and a concrete base. It’s the same sign visible in Steinau’s iconic photograph of the meeting before the riot.

Sources

Peterson, Bill. “The Hurricane’s Eye: 28th and Greenwood.” Courier Journal. May 29, 1968: A1.

Branzburg, Paul M. “West Enders Urge Boycott of Two Firms.” Courier Journal. October 19, 1968: B1.

“Would-be Robbers Find No Cash.” Courier Journal. June 13, 1975: B16.

Johnson, Ben. “Riot’s Anniversary: Racial Progress Here is Measurable.” Courier Journal. May 28, 1978: D1.

Simon Meiners

Communications & Research Specialist

Frazier Museum Present Black Lung Project 2022 Kentucky History Award

Historians, unite!

Last month, I attended the annual National History Day (NHD) state competition in Lexington, Kentucky, as a representative of the Frazier. National History Day is an academic program that encourages students to examine history in unique and engaging ways. According to the NHD website, participants range from sixth to twelfth grade and primarily focus on “historical research, interpretation, and creative expression.”

Toward the end of the school year, students attend local, regional, and national competitions to display historical projects related to the year’s given theme. This year, the 2022 theme is “Debate and Diplomacy in History: Successes, Failures, Consequences.” I attended this year’s Kentucky state competition in order to award a student group the Kentucky History Award on behalf of the museum. My priority was to determine which project has the strongest ties to the Bluegrass State and whether the project addresses a historically unrecognized perspective.

There were several fascinating projects to choose from, but I ultimately decided on the project “Black Lung: Failed Prevention and the Fight for Compensation.” The recipients created a historical skit that depicts a family seeking compensation for work-related sickness as a result of working conditions in the coal mines. The project sets out to highlight the challenges for coal miners in claiming their benefits. The student group has an impressive resource page, full of interviews with individuals of varying ties to the coal industry. Additionally, the students express their desire to address a topic with strong ties to their community.

Members of the Junior Performance Group prepare for their first interview with black lung lawyer Gene Siler, October 2021. From left, Logan Stepp, Hailey Sanders, Nicholas Stewart, and Blake Burnett. Credit: Ann Stepp.

To learn more about the group’s project, read the following interview for insights into how they chose the topic and their process of putting it together.

What gave you the idea for your topic?

“We wanted to choose a topic that was something important to the area where we live, in Southeast Kentucky. All of us have family members that have been coal miners or are now. We have grown up hearing stories of how the coal companies try to avoid responsibility for mistakes made on the job. Black lung is one of these mistakes.”

How did you decide whom to interview?

“We started the interview process with miners we knew were impacted by black lung. One of them gave us the name of the lawyer and the doctor that really helped us understand the process of fighting for benefits. It was a judge at the region level that recommended we conduct interviews to show the “other side” of the debate. Through family contacts, we found the president of a local coal company and a lawyer in Pineville that represents them. We wanted to interview anyone connected with coal mining to better understand both perspectives. Coal mining is such an integral part of our culture that it was relatively easy to find people to interview in our area.”

Why is this topic important for people to learn about?

“This isn’t just a problem in Kentucky. Coal miners everywhere are affected by black lung and there isn’t much awareness about their situations. Not only does it take years for the miners to get their benefits, but the trust fund that their money comes from in America is running out. This means that they have to fight for the renewal of the trust fund, as well as combat the companies that are responsible.”

What do you want the audience to take away from your presentation?

“Our project was an attempt to bring light to the topic of black lung and coal mining. Although this was a big debate in our area, many aspects of coal mining and the difficulties miners faced have been forgotten or never acknowledged. Many coal companies sought to silence miners and make it seem like they were never in the wrong. Though there were many attempts at diplomacy, the solutions were only temporary.”

The 2022 NHD national contest is scheduled for June 12–16, 2022. Visit the contest page for more details!

Shelby Durbin

Education & Engagement Specialist

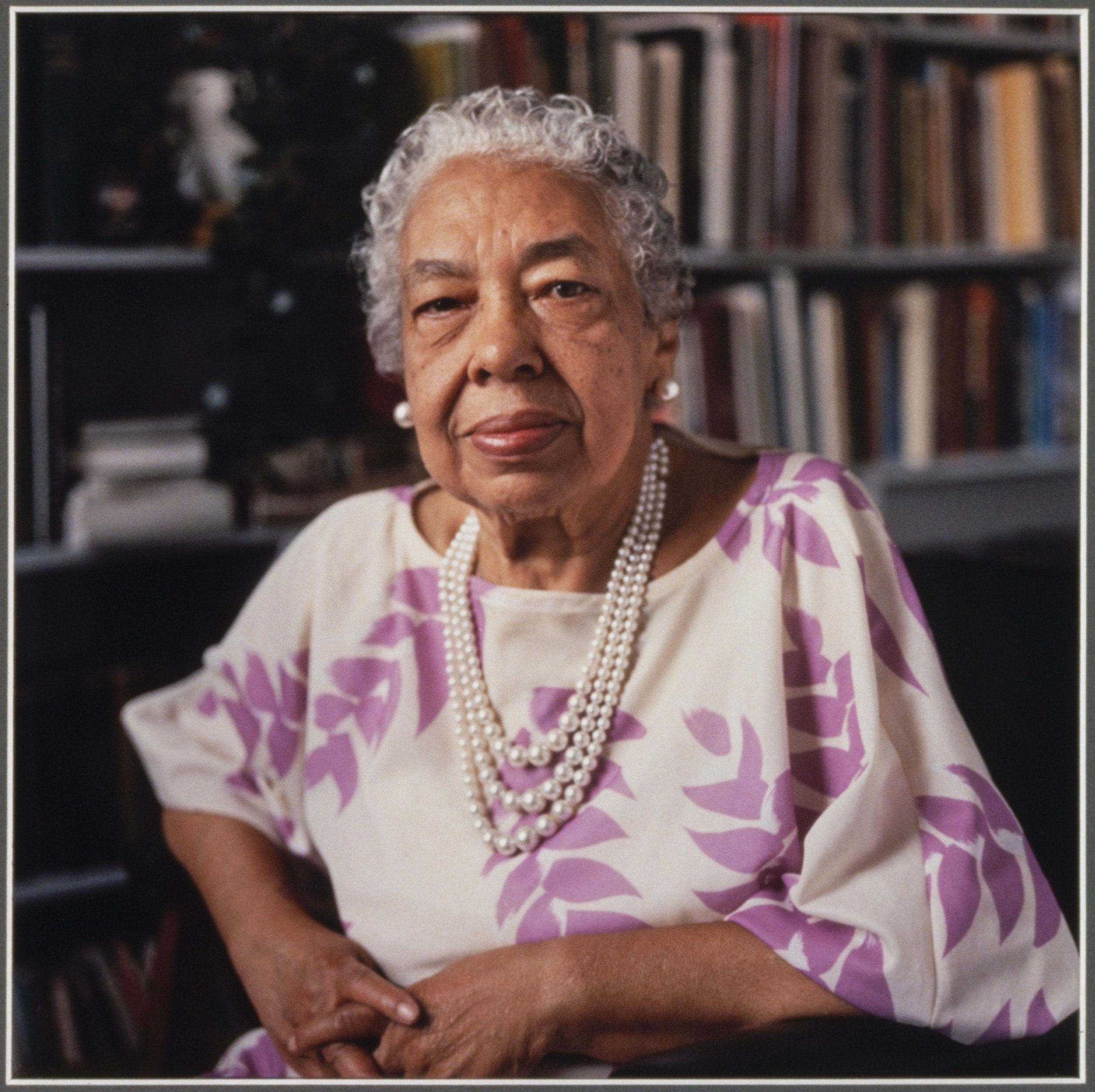

Notable Kentuckians: White House Press Corps Journalist Alice Allison Dunnigan

With recent news of Karine Jean Pierre being appointed as the first Black and openly gay White House press secretary, it might be worthwhile to look back on where this began. Because the throughline to Jean Pierre arguably started in Kentucky with Alice Allison Dunnigan. Born April 27, 1906, in Russellville, Kentucky, Dunnigan was the child of sharecroppers who at an early age took to writing and reporting. She wrote her first newspaper article at the age of thirteen.

In the 1930s, as a young woman feeling unfulfilled by domestic life in the country, Dunnigan moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a freelance writer for the American Negro Press by day, while taking courses at Howard University at night. By the end of WWII, Dunnigan was working as the Washington correspondent for one of the premier Black newspapers of the period, the Chicago Defender.

In 1947, Dunnigan sought press credentials to cover US Congress and the Senate. After receiving some resistance from the non-government-affiliated group known as Standing Committee of Correspondents (which granted such credentials), Dunnigan finally received those credentials. A year later, Dunnigan became the first Black American to ever receive a White House press credential.

Poster located near the second floor landing of the Frazier commemorating Dunnigan as the first Black White House correspondent, May 19, 2022. Pictured is a banner that was commissioned by the Frazier in 2020. Made in collaboration with Laurie Youngkin and her students at Ballard High School, the banner was created for the museum to celebrate the temporary exhibition What is a Vote Worth? Suffrage Then and Now. Credit: Brian West.

While with the White House Press Corps, Dunnigan covered Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Despite facing racism in D.C.—like not being allowed in certain whites-only establishments to cover President Eisenhower and being forced by Eisenhower himself to submit her questions to him ahead of time (even though none of the other correspondents had to do so)—Dunningan persevered and remained a fixture in the White House Press Corps into the 1960s.

After leaving the Corps in the early 1960s to campaign for and then work with President Lyndon B. Johnson, Dunnigan retired from public life in 1970. She died at age seventy-seven in 1983.

Statue of Alice Dunnigan installed on the grounds of the SEEK (Struggle for Emancipation and Equality in Kentucky) Museum in Russellville, Kentucky, July 24, 2019. Credit: SEEK Museum, Wikimedia Commons.

Yet, even after death, her legacy lives on. In 2019, a statue of her was installed by the SEEK museum in Russellville. And just this month, the White House Press Corps Association named an award in her honor. So, the appointment of Karine Jean Pierre could be seen as the fulfillment of what Alice Dunningan had worked so hard for long ago.

Brian West

Teaching Artist

2022 Owsley Brown Frazier Classic Sporting Clay Tournament Early Bird Prices End May 31

It is never too early to start planning for the future—in this case, Friday, September 30: the day the Frazier will host the seventh annual Owsley Brown Frazier Classic Sporting Clay Tournament!

Graphic for Owsley Brown Frazier Classic Sporting Clay Tournament. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

The Sporting Club at the Farm, undated. Credit: The Sporting Club at the Farm.

This year’s event will have a new home, The Sporting Club at the Farm in New Albany, Indiana, just fifteen minutes from the museum.

The event, named in honor of the founder of the Frazier History Museum, his broad philanthropic investment in the Louisville community, and his lifelong love of history and the artistry of the gun, the Classic will feature 12- or 20-gauge shotguns on the 15–20 station/72-target sporting clays course.

Participants will spend the day competing before a delicious catered lunch, featuring Bourbon, craft beer, a raffle, and a silent auction of premium Kentucky Bourbons and exclusive Kentucky and Southern Indiana experiences. The tournament uses Lewis Class scoring, which allows all skill levels the opportunity to win awards.

Join an amazing community of people who know how to have a fun time ALL for a great cause! All proceeds support Frazier’s exhibitions, educational outreach, and programs. Register by May 31 to receive the Early Bird special pricing of $250 for individuals, and $1,000 for teams. Starting June 1, prices will be $300 for individuals, and $1,200 for teams. So don’t delay—register now for the Early Bird special!

Thank you to our early sponsors, iAmmo and Republic Bank and Trust. For information on becoming a sponsor, contact Lonna Versluys at LVersluys@fraziermuseum.org.

Amanda Egan

Membership & Database Administrator

Bridging the Divide

Notable Kentuckians: Mental Healthcare Activist Cornelia Atherton Serpell, 1917–2011

May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and the global pandemic has only exacerbated the need for awareness. Reports indicate that during the first year of the pandemic, global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by a whopping twenty-five percent. Mental Health Awareness Month was started back in 1949 as a way to help eliminate the stigma associated with mental illness. We have made progress, but we certainly have more work to do. We wanted to share the story of Cornelia Atherton Serpell, a Louisville woman considered a mental healthcare activist who spent her life as a champion for the cause. Her story is told by Alexandra Luken, the executive assistant at Cave Hill Heritage Foundation. It’s part of our partnership with Cave Hill Cemetery to bring you the stories of notable Kentuckians buried at Cave Hill who deserve our attention.—Rachel Platt, Director of Community Engagement

On the precipice of disaster, mental healthcare in Kentucky found a fierce advocate in Cornelia Atherton Serpell. She dedicated her life’s work to championing sweeping changes in how mental health illness was perceived and treated and eliminating barriers to healthcare in rural Kentucky.

Cornelia Atherton Serpell, undated. Credit: Alexandra Luken.

Cornelia Atherton Serpell grew up in a family where community activism was a family trait and expected. Both her grandfather and father served in the state legislature. Her grandfather, John McDougal Atherton, founder of Atherton Distillery, was a champion of public education. Her father, Peter Lee Atherton, was instrumental in getting parole and probation laws written into Kentucky statutes. Her mother, Cornelia Anderson Atherton, received Britain’s King’s Medal for the Cause of Freedom for her work with the Bundles for Britain program during WWII, modeling for her daughter the virtue of leveraging social and political status with diplomacy and the skills of arbitration, negotiation, and the navigation of channels to build consensus for public service causes.

While a student at Sarah Lawrence College in 1937, Cornelia Atherton Serpell first read a shocking series of nationally acclaimed articles in the Louisville Courier Journal, her hometown newspaper, about the treatment of the mentally ill, which described it as a “living death.” In 1939, she attended a lecture sponsored by the Junior League of Louisville about the best and worst state mental hospitals across the country. When she asked what she could do, it was suggested that she start a recreation program for patients at Lakeland (later Central State Hospital), for which there was no money in the budget. Patients confined to straitjackets for days on end, or chained to the wall, naked and unable to stand up, hosed down by the staff to keep them clean were the norm in facilities like these at that time. No medications were given to patients; psychiatry was in its infancy. The horrifying conditions were jolting to Serpell, who began volunteering at the hospital, often as frequently as five days a week.

She began working as an unpaid independent lobbyist for mental health causes during the General Assembly, making every legislator aware that it cost more money to board her dog at the vet per day than the state paid per day to feed, house, and care for a mentally ill person. Through her persistent efforts, the budget for people with mental illness was increased. The state set up a separate Department of Mental Health in 1952. Serpell also helped create the Kentucky Association of Mental Health in 1948, and served as its president.

Serpell worked hard to get mental health into the mainstream of general health, and to remove the criminalization and stigmatization of mental health issues. Her focus included the inclusion of basic psychiatric training for general practitioners and a process for the treatment of mental disorders.

She served on many state and local councils and boards dealing with mental health, health planning, and aging, including the Bingham Child Guidance Clinic, the Jefferson County Alcohol and Drug Abuse Center, Bridgehaven, Visiting Nurse Association, the Kentucky Commission on Aging, the State Board of Medical Licensure, Council for Health Services, and the Kentucky Legislation Ethics Commission, and received numerous awards recognizing her life-long work in the field of health services.

Some of the many awards and recognitions received for her service include: the Distinguished Alumna Award from Louisville Collegiate School, the Health Kentucky: Service to Humanity Award, the Kilgore Good Samaritan Award, and the President’s Award for the Kentucky Association of Health Care Facilities.

Cornelia Atherton Serpell died in 2011. She is interred in Section 13, Lot 110, at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

Alexandra Luken

Executive Assistant, Cave Hill Heritage Foundation

Guest Contributor

History All Around Us

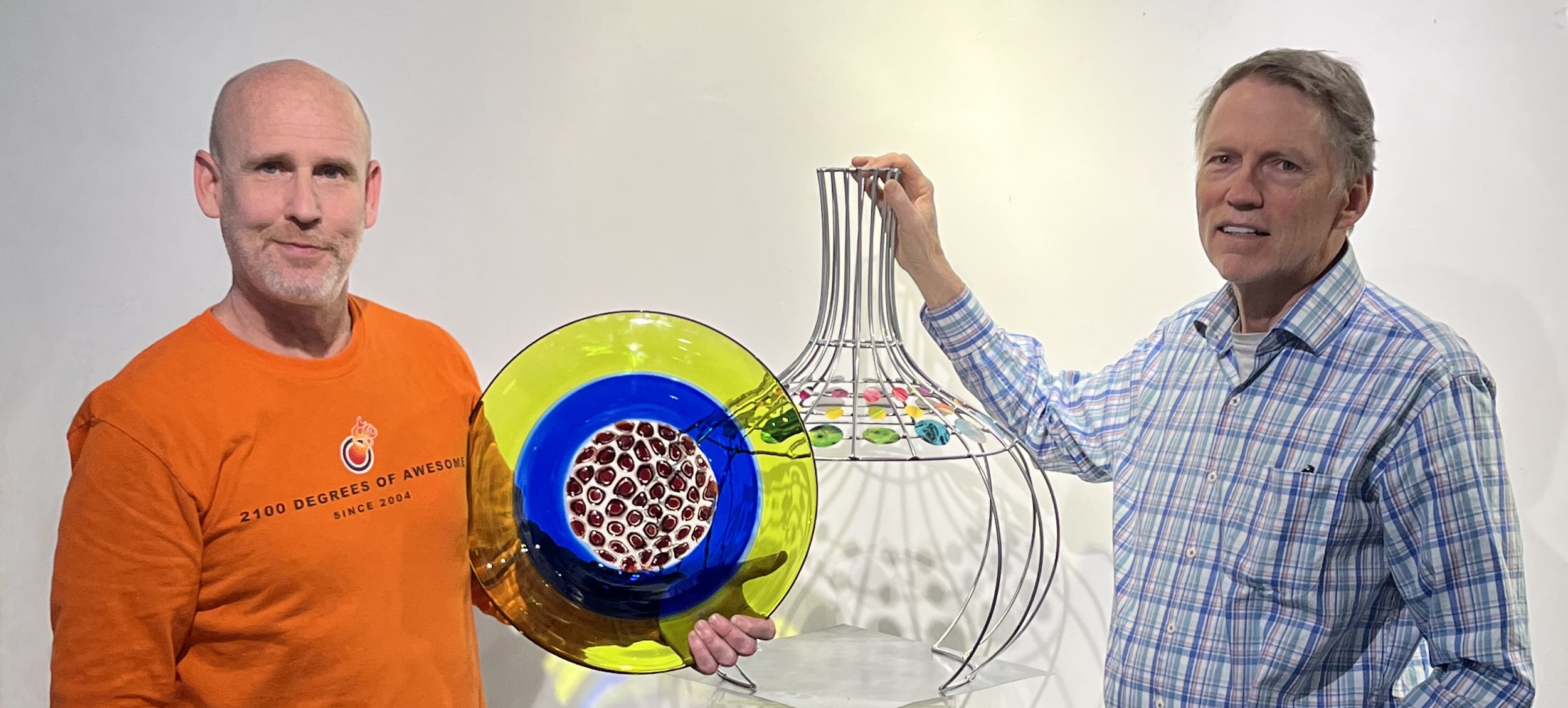

Dave Caudill on Stephen Rolfe Powell Memorial Sculpture Garden at Center College

Say the name Stephen Rolfe Powell and most glass artists in Kentucky will tell you of some connection to him. Many will tell you he was a mentor, and most of all, a friend. Glass artist Ché Rhodes, who was featured earlier in today’s newsletter, said Powell was all of those things to him.

From left, Stephen Rolfe Powell and Ché Rhodes, undated. Credit: Ché Rhodes.

Powell made many of those connections as an alumnus and long-time faculty member at Centre College. Powell passed away in 2019, and now those he impacted are coming together to honor him with the Stephen Rolfe Powell Memorial Sculpture Garden at Centre. Local artist Dave Caudill explains his involvement in the garden, and one person who was key in leading this beautiful tribute.—Rachel Platt, Director of Community Engagement

Noted glass artist Brook Forrest White Jr. has selected me to help him build his remarkable memorial to Stephen Rolfe Powell at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. Powell was an internationally renowned glassblower, professor at Centre, and mentor to Brook.

Artist’s rendering of the Stephen Rolfe Powell Memorial Sculpture Garden at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, undated. Credit: Centre College.

From left, Brook Forrest White Jr. and Dave Caudill, undated. Credit: Dave Caudill.

The memorial will feature an illuminated stainless steel and blown glass sculpture that stands twenty-five feet tall, benches which feature some of Powell’s glass slabs, a colorful landscaped garden, and an outdoor classroom. We will be building the sculpture this summer and dedicating it this fall.

Brook’s work can be seen at his Flame Run studio in the Glassworks building in Louisville as well as in many public spaces in Kentucky. His beautiful work has been widely collected.

The ambitious project is being made possible by philanthropic support from Powell’s friends and former students and the Corning Inc. Foundation. Construction began in April 2022, with the goal of completion by the fall, followed by a dedication ceremony to be held during Homecoming 2022. This time frame also coincides with a retrospective exhibit of Powell’s glass work at the Art Center of the Bluegrass in Danville.

Dave Caudill

Artist

Guest Contributor

On This Date: Beverly Hills Supper Club Fire in Southgate, May 28, 1977

This Saturday will mark the forty-fifth anniversary of one of the deadliest nights in the history of the Commonwealth. On Saturday, May 28, 1977, over 160 people died from injuries sustained during the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire in Southgate, Kentucky, located seven miles south of Cincinnati.

Overhead view of the Beverly Hills Supper Club after the fire, c. May 29, 1977. Published on page A1 of the May 30, 1977, issue of the Courier Journal. Credit: Robert Steinau, Courier Journal.

The fire occurred at the most popular nightspot in Northern Kentucky at the time. In operation since the 1930s, the Beverly Hills Supper Club had expanded from a small venue in the 1940s into a 1.5-acre Vegas-style entertainment complex, hosting acts like Bing Crosby and James Brown and offering an event space for weddings, school dances, and private dinners.

It also was in operation during a time when fire codes in the US were not uniformly enforced. In addition, the fire safety tools one might take for granted today, such as smoke alarms, exit signs, and sprinkler systems, were not in use at the club in 1977.

To add even more fuel to the fire, that night saw the Supper Club booked over capacity, perhaps intentionally so. It was Memorial Day weekend, after all, and John Davidson was the headliner. The club, which had a capacity for only 1,500 people, had upwards of 2,600 to 3,000 people inside.

A floor plan of the former Beverly Hills Supper Club, from “Richard Bright - Appendix C: Richard Bright’s Analysis: An analysis of the development and spread of fire from the room of fire origin (Zebra Room) to the Cabaret Room.” Beverly Hills Supper Club Fire. Center for Fire Research, United States National Bureau of Standards. Credit: Wikipedia.

The fire began near the entrance to the supper club at 8:45 p.m, in “the Zebra room,” near where a wedding rehearsal was taking place. After the participants in the adjacent room had complained of excessive warmth and loud popping sounds, their room was evacuated, and staff tried to get the smoke out of the Zebra Room. But because no one—not even club staff—knew exactly where the smoke was coming from in the Zebra Room, the fire spread quickly to the back of the building. Due to the lack of sprinklers and smoke alarms, virtually no one in the back of the complex was made aware of what was going on until it was too late.

An usher had to come to the main entertainment hall, “the Cabaret Room,” near the back of the building, to notify patrons that there was a fire in the club and that everyone should leave. However, many of the attendees decided to stay and continued watching a warmup act before John Davidson was to perform. Unfortunately, Davidson never got to go on stage to perform.

By 9 p.m., the entire complex was on fire and the smoke had reached the Cabaret Room. And though fire departments from Kentucky and Ohio—including Willie Snow, a firefighter featured in the Frazier’s Cool Kentucky exhibition who came to the aid of visitors trapped by the fire—came to the rescue, there still were a number of fatalities.

Eyewitness accounts described one scene in which people who were able to free themselves from the jam of people who were caught in the Cabaret Room trying to escape, had just stepped out into the open air, before immediately collapsing upon the ground unconscious. Firefighters and EMS had found that those who did collapsed had the tell-tale sign of black stains underneath their nostrils: Their lungs had been burned from the inside out by the smoke.

By night’s end, over 160 people had died and 200 people had been injured. Because of the fire, new fire code standards were passed in Kentucky and across the country, making the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire a tragic yet pivotal moment in the history of fire and safety code regulations.

Brian West

Teaching Artist