New Member November, 1930s Paper Mâché Halloween Pumpkin, Gay Poems for Red States, and More

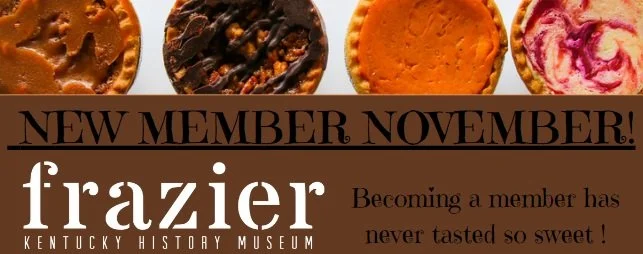

Get ready for New Member November! I’m thrilled to announce the details of our month-long membership drive. But first, won’t you be my sugar pie?

Starting today and ending November 17, all new members will receive a free Frazier Specialty Pie from Georgia’s Sweet Potato Pie Company! We wanted to create something extra-sweet for new members.

Georgia’s will create a one-of-a-kind Frazier Specialty Pie free for new members only. This delicious fall creation is made from the fusion of a new s’mores-flavored spirit named Mash and Mallow that is set to launch this Wednesday! The recipe consists of Mash and Mallow–inspired chocolates housed in a graham cracker crust topped with a Mash and Mallow–flavored toasted marshmallow meringue.

Is your mouth watering yet? Mine is!

If you’re a current or renewing member, you can purchase a Frazier Specialty Pie now through November 17 and receive 15% off your entire order (not applicable for online or Thanksgiving orders) when you visit Georgia’s at 1559 Bardstown Road. To guarantee freshness, the pies will be available for pickup the next three Fridays:

November 3, 11 a.m.–7 p.m.

November 10, 11 a.m.–7 p.m.

November 17, 11 a.m.–7 p.m.

I’ll email new, current, and renewing members vouchers so you can redeem your free or discounted products.

So, who’s ready for New Member November? I am! Come see me at Georgia’s this Friday, November 3, between 3 and 6 p.m. I’ll have an extra gift of appreciation for those who visit during that time!

Gather your friends, coworkers, and neighbors to join the Frazier Family—because, here at the Frazier, we like to have our specialty pie and eat it, too! Halloween is tomorrow, so treat yourself by becoming a member or renewing today.

In today’s Frazier Weekly, keep reading to see what creepy items lie in our Curator’s Corner and gather some last-minute costume ideas from our Museum Shop. Plus, hear how the limelight has turned to Kentucky recently with Bellarmine alum Brandon Pfaadt leading the Diamondbacks to the World Series and how Netflix has a new series highlighting Louisville’s Ohio Valley Wrestling.

Amanda Egan

Membership Manager

Frazier History Museum

This Week in the Museum

Curator’s Corner: Creepy Paper Mâché Pumpkin, 1930s

Paper mâché pumpkin, 1930s. Part of the Frazier History Museum Collection. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

The celebration of Halloween was brought to Kentucky with Scottish and Irish immigrants in the mid-1800s. Until trick-or-treating became popular in the 1920s and `30s, Halloween was primarily celebrated by adults and the creepy decorations reflected it. Decorations were primarily made of paper and paper mâché and meant to be discarded after the holiday. The decorations, however, also reflected the time. Black cat decorations feature exaggerated features reminiscent of blackface and minstrel shows of the Jim Crow Era. Halloween decorations became more kid-friendly after World War II, with Maimie Eisenhower decorating the White House for the first time in 1958.

The traditional jack-o-lantern originates with Celts, who carved faces in turnips to help ward off evil spirits. When the tradition came to the United States, a native vegetable was used: the pumpkin. However, the specific variety we think of today, with thin and easily carved walls and a large stem, was not developed until the 1960s.

The creepy pumpkin pictured here was donated to the museum just last year. Made of paper mâché, it dates back to the 1930s.

Happy Halloween!

Amanda Briede

Sr. Curator of Exhibitions

Museum Shop: Hats for Halloween

Get your historic Halloween style on point with Honest Abe’s top pick, Daniel Boone’s favorite cap, or this nifty bonnet! Each is perfect for some historical hijinks. The hats are available in the Museum Shop and online.

Frazier+ Video of the Week: Magician Thomas Tobin’s Disappearing Act

Now the Frazier fits in your pocket! Curated by the museum’s education team, the mobile app Frazier+ provides engaging and educational Kentucky history content—free of charge. Users can explore the museum’s collection of videos, photos, and texts to either heighten their in-person experience or learn from the comfort of their couch or classroom. The free app is available for download for Android and iOS devices through the App Store and Google Play.—Simon Meiners, Communications & Research Specialist

Thomas Tobin (1844–83) was an ingenious man who pioneered some of magic’s most mind-bending illusions of the 1800s. A series of events led the British man to Kentucky, where he stayed and worked as an educator until his untimely end. For nearly a century, no one in the magic community knew of his final resting place. The mystery ended here in Louisville, as you’ll see in this Frazier+ video.

Mick Sullivan

Curator of Guest Experience

Musical Kentucky: A Song from each County, Nicholas–Pulaski

As a supplement to our Cool Kentucky exhibition, we’re curating a Spotify playlist of 120 songs: one song from each county in Kentucky. In 2023, once a month, we’ll share songs from ten counties, completing the playlist in December. For October, we’re sharing songs from these counties: Nicholas, Ohio, Oldham, Owen, Owsley, Pendleton, Perry, Pike, Powell, and Pulaski.

Mean by Taylor Austin Dye, 2019. Credit: Taylor Austin Dye.

Clear Waters Remembered by Jean Ritchie, 1970. Credit: Sire.

Mountain Soul by Patty Loveless, 2001. Credit: Jahaza Records.

“Home” by Joan Shelley. (Released June 24, 2022.) Founded in 1849, Goshen is a riverfront community in Oldham County named for the Biblical land the Hebrews departed at the time of the Exodus. Today, it’s home to horse farms and a 168-acre nature preserve with grasses, wildflowers, songbirds, streams, and ravines. Goshen-native roots musician Joan Shelley wrote “Home” about her upbringing.

“Mean” by Taylor Austin Dye. (Released December 13, 2019.) “Mean” is Booneville, Owsley County, artist Taylor Austin Dye’s ode to the world’s best-selling Kentucky Bourbon. “If I drink a shot of whiskey, Katie bar the door / And if I think you’re lookin’ at me, we’ll wind up on the floor / Kissin’, cussin’, fightin’, fussin’, everything in between / I just can’t help it, baby: that Jim Beam makes me mean!”

“Black Waters” by Jean Ritchie. (Released 1970.) The youngest of fourteen children, folk icon Jean Ritchie (1922–2015) of Viper, Perry County, grew up singing ballads her ancestors had brought from England, Scotland, and Ireland. On “Black Waters,” she skewers the coal tycoons who’ve poisoned her land. “If I had ten million, somewhere thereabout / I’d buy Perry County and run them all out.”

“You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive” by Patty Loveless. (Released June 11, 2001.) In 1997, Darrell Scott wrote a now-iconic song about the plight of Harlan County coal miners. In 2001, Pikeville, Pike County’s Patty Loveless recorded a rendition. “In the deep dark hills of Eastern Kentucky / That’s the place where I trace my bloodline / And it’s there I read on a hillside gravestone / “You’ll never leave Harlan alive.””

“How Many Biscuits Can You Eat?” by the Coon Creek Girls. (Released 1968.) On June 8, 1939, the all-women string band the Coon Creek Girls, fronted by Pinch-em-tight Hollow, Powell County, fiddler Lily May Ledford (1917–85), performed “How Many Biscuits Can You Eat?” during a set at the White House for Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and their guests King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of England.

Simon Meiners

Communications & Research Specialist

Trinity, Bellarmine Alum Brandon Pfaadt to Make World Series Debut Tonight

As a former sportscaster, my husband always follows the World Series. But this year’s series, which started over the weekend with two games in Texas, has him glued to the TV set because a former student of his is in the spotlight. That young man, Brandon Pfaadt, will make his World Series debut in Arizona tonight as the starting pitcher for the Diamondbacks! I’ll let my husband tell the story. It’s the perfect story to tell as the Frazier continues to spotlight the sports figures in our Kentucky Rivalries exhibition, which closes December 6. Now, to the World Series and our local Diamondback who is shining! You can watch his debut tonight, 8 p.m., on WDRB.—Rachel Platt, VP of Mission

Brandon Pfaadt (pronounced “Fot,” which rhymes with “not”) has become one of the inspirational stories of the postseason for Major League Baseball. The success on the mound of this Trinity High School and Bellarmine University alum has helped propel the Arizona Diamondbacks into the World Series.

Pfaadt was the starting pitcher for Arizona in game three of the National League Championship Series (against Philadelphia). In that outing, he pitched into the sixth inning while giving up no runs and striking out nine. He was the winning pitcher for the Diamondbacks in that game.

He got the start again in the seventh and deciding game of the series and in that outing struck out seven batters in four innings.

Pitcher Brandon Pfaadt takes the mound for the Bellarmine Knights, c. 2018–20. Credit: Bellarmine University Athletics.

He pitched at Bellarmine from 2018 to 2020. In his final season at BU (2020), he had a record of 3-1 (in five starts) with 27 strikeouts over 26 innings pitched. After those five starts, the coronavirus pandemic cancelled the remainder of the season.

I met the 25-year-old Pfaadt back when he was an 18-year-old freshman at Bellarmine. He was a student in my Public Speaking class.

The things I remember about him was he was always in class, always on time, always prepared, and a solid student. If he knew he had a future in Major League Baseball, he never let on. Even though he was a very talented pitcher in college, he was humble, friendly, and an excellent student (at least he was in my class; I can’t speak for his other classes but would be surprised if any of his other instructors said otherwise). He was exactly what you would want in a student-athlete.

And because of my experience with him in the classroom, it makes it easy for me to be excited for him and cheer for him as he continues to try to make his mark in Major League Baseball.

Even though his success at this level is still all new, I would think even if he has a long, successful career in Major League Baseball, he will remain the same person I remember as an 18-year-old freshman in my class. And those humble qualities are why I would hope everyone will cheer for his continued success.

Gary Fogle

Instructor, Department of Communication, Bellarmine University

Guest Contributor

From archrival teams like the Cats and the Cards to dueling editors, competing caves, and beefing barbecues, the Frazier’s exhibition Kentucky Rivalries celebrates the most iconic conflicts in the Bluegrass State. At lease one of those conflicts erupted into violence, when, on July 21, 1857, rival newspaper editors George D. Prentice and Reuben T. Durrett dueled on Third Street in Louisville. We’ve asked Western Kentucky historian Berry Craig to write about that infamous duel, gunslinger Prentice, and his Henry rifle, which is on display in Kentucky Rivalries. Be sure to see it before the exhibition closes December 6.—Simon Meiners, Communications & Research Specialist

1860s George D. Prentice Henry Repeating Rifle on display in the Frazier’s Kentucky Rivalries exhibition, December 4, 2022. Credit: Berry Craig.

George D. Prentice’s old Henry repeating rifle is on display at the Frazier.

But a pistol was the firebrand Louisville Journal editor’s weapon of choice. At least it was on a busy Falls City street on July 21, 1857—the day he shot it out with Reuben T. Durrett, editor of the archrival Louisville Courier.

Evidently neither one was hit. Prentice purportedly wounded a bystander in the leg.

The Henry rifle was one of the deadliest weapons on the Union side in the Civil War. Most Yankees and rebels packed single-shot, muzzle-loaders.

Prentice’s name is engraved on the rifle, though misspelled: “George D. Prentise, Louisville, KY.”

The Henry, invented in 1860, may have been a gift for his important role in keeping Kentucky under the Stars and Stripes in 1861–65. The Journal was the state’s leading pro-Union paper; the Courier was the chief Confederate organ.

Portrait of George D. Prentice, undated. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Reuben T. Durrett, 1908. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

For years, a stone statue of Prentice greeted patrons at the Louisville Free Public Library. The likeness was controversial.

Before America’s most lethal conflict, Prentice authored virulently anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic editorials. The Journal’s rabid nativism was blamed for helping incite Protestant Know-Nothing mobs to rampage through German and Irish neighborhoods on election day, August 6, 1855. Dubbed “Bloody Monday,” the mayhem resulted in twenty-two deaths and widespread property damage.

Prentice, like most Kentucky Unionists, was pro-slavery, pro-Union, and anti-Lincoln—and he saw no contradiction in that position. (Lincoln received just 1,366 votes in his home state when he was elected in 1860.)

Prentice’s gun battle with Durrett stemmed from a July 20, 1857, Journal article which claimed Democratic Congressman John Milton Elliott of Prestonsburg was a drunk. Elliott was a Courier favorite.

The next day, the Courier published an article that jabbed the Journal’s “Plug Ugly editor” and his paper, “the principal Plug Ugly organ in Kentucky.”

The Courier confessed it knew nothing of Elliott’s drinking habits. The paper countered that Prentice was a “notorious drunkard” who got so liquored up on a ferryboat that he fell off the gangplank and had to be pulled from the Ohio River.

Prentice, in high dudgeon, immediately dashed off a letter to Durrett. He suspected the article was Durrett’s dirty work and demanded to know if he would retract it in the next issue of the Courier.

Durrett quickly replied. His missive denied that Prentice had any “right to interrogate me as to the authorship of any article in the Courier unless you see my name at the head of its columns as editor.”

The editors swapped more poison pen letters. Finally, Prentice threatened to shame Durrett publicly.

“I shall denounce you to your face the first time I see you upon the street. I shall be upon Third cross street myself in half an hour or less, and I hope I shall not have to wait for you long.”

On July 21, guns blazed at the appointed time. After the smoke cleared, the bystander presumably went for medical aid, and the two editors went back to work.

Naturally, Durrett and Prentice disagreed on how their gun battle went down, and they published wildly disparate versions of the rencontre.

The Journal claimed Durrett was a coward who hid and fired at Prentice from behind a door. The Courier claimed “Mr. Prentice was very much intoxicated.” Durrett and Prentice resumed their war of words.

The Journal and the Courier dueled in print throughout the secession crisis until September 1861, when authorities shut down the Courier as treasonous. When Durrett was hauled off to prison, Prentice was among those pleading for his release. Publisher Walter N. Haldeman—after whom the Haldeman Street off Frankfort Avenue is named—escaped to the Confederates. He returned after the war and bought out the Journal; in 1868, he started the Courier Journal and kept Prentice on the payroll as a junior editor.

Berry Craig

Professor Emeritus of History, West Kentucky Community and Technical College

Guest Contributor

Bridging the Divide

Willie Carver Jr. on Gay Poems for Red States

In August, while vacationing in Eastern Kentucky, I told the clerk at Coffee Tree Books in Morehead I was searching for Kentucky books. She suggested I buy Willie Carver Jr.’s autobiographical 2023 title Gay Poems for Red States, which offers a window into the life of a boy growing up in Eastern Kentucky in the 1990s. A teacher for seventeen years in Mt. Sterling, Montgomery County, Carver was named the 2022 Kentucky Teacher of the Year. However, shortly before the book’s publication, he’d quit the profession, citing a lack of support for himself and other LGBTQ teachers. I was incredibly moved by Carver’s poems, so I invited him to write for Frazier Weekly about his book and the challenging circumstances in which he wrote it. You can purchase a copy at Carmichael’s Bookstore or the University Press of Kentucky.—Simon Meiners, Communications & Research Specialist

Front cover of Gay Poems for Red States by Willie Carver Jr., 2023. Credit: University Press of Kentucky.

Earlier this month, I was honored to headline the Voices of Winchester event at the Leeds Center in downtown Winchester. A converted movie theater turned arts center hosted local storytellers who spoke about their pasts and the ways in which those pasts create some sense of hope for their town and state’s present and future.

Perhaps the most captivating storyteller was Mrs. Jane Burnam, who told the story of Fannie Cole, a woman born a slave whose husband bought her freedom when she was in her fifties, and who, in her short two decades of freedom in Winchester, Kentucky, was able to live more and do more good than most of us will ever manage. One particular sentiment expressed by Mrs. Burnam, a Black woman who stood before us at nearly the same age as Fannie Cole was when she died, struck me: “When I was young, I didn’t much care for history because history was never about people like me, about people who looked like me, about people who came from where I come from. History was about other people. Fannie changed that.”

I don’t exactly come from where Mrs. Burnam comes from or look like her—I am a tall, white, middle-aged, gay Appalachian man from Eastern Kentucky. But I understood that sentiment—the idea that there are parts of this world not meant for me, even when they claim to be.

School promised to be a place where I belonged, so much so that I became a teacher, a profession that I loved so much and dedicated so much heart to that I was named Kentucky Teacher of the Year. It was the honor of a lifetime, because I know the hard work and dedication of Kentucky’s 40,000 public school teachers. Despite the honor, this moment brought to head that same feeling that Mrs. Burnam hinted at—that the past cannot be escaped when it hasn’t been confronted, and suddenly almost two decades of working within a system that I loved but that consistently excluded and failed its Black, brown, and queer students, came to a head: extremists noticed me and attacked me and my LGBTQ students, and my school district let them.

Certain teachers and certain students were worth defending. Not the queer ones.

Gay Poems for Red States is a response to that, a collection of narrative poems about my childhood. It is a remembering of those spaces I, as a young queer hillbilly, wanted to exist in and was denied. It is a remembering of a life that is not written in stories or history books because it was never deemed worthy. I hoped to remind others, and myself, that their lives deserve dignity, deserve a story, deserve being heard, whether or not politicians think they deserve to be written down or allowed to be read.

This collection is a raw and complicated love letter to Appalachia, written with fire in its ink. Above all, it was a chance to give a queer kid who was silent so that I might live the chance to finally speak, and to say to people who look and sound like him, who come from where he comes from, that their stories, their history, and their voices matter.

Willie Carver Jr.

Author, Gay Poems for Red States

Guest Contributor

History All Around Us

From the Collections: Louisville Wrestler Jim Mitchell Objects

Last year, author John Cosper donated several objects from midcentury Louisville wrestler Jim Mitchell to the Frazier Museum. Cosper has written several books about the history of wrestling in Louisville and Kentucky. (In fact, one of the subjects of his 2017 book Louisville’s Greatest Show is my grandfather Mel Meiners, who wrestled in the 1950s under the name “Schnitzelburg Giant”!) Known as the “Black Panther,” Mitchell wrestled from the 1930s to the `60s. We asked registrar and manager of collections engagement Tish Boyer to discuss some of the Mitchell objects in our collections.

Simon Meiners

Communications & Research Specialist

To borrow some professional wrestling jargon: Wrestlers doesn’t quite “get over” as a “work.” More on that later. First, the setting of the new Netflix docuseries, Ohio Valley Wrestling (OVW), should be established.

Located at 4400 Shepherdsville Road in Louisville, Ohio Valley Wrestling is the latest in a long line of wrestling promotions that has called the Falls City home. In fact, pro wrestling in Louisville goes all the way back to the 1880s, when an up-and-coming athlete could challenge a wrestling champion to a match by posting an ad or writing a letter to him in the Courier Journal.

According to local pro wrestling historian and author John Cosper, even then the outcomes of those professional wrestling matches were predetermined. Promoters and wrestlers would work together and host matches, lasting several hours and containing multiple falls or rounds, like in a boxing fight. The parties would determine which side had received the most money bet by the later rounds, and then “decide the finish based on would could win the more money.” Even then professional wrestling was a “work.”

Over time, several independent promotions—a few homegrown, most produced by promoters from other wrestling territories—would pitch a tent in Louisville: from Heywood Allen’s Athletic Club of the 1930s–50s, which hosted matches at the Armory (now the defunct Louisville Gardens) and segregated matches at the Savoy Theater at 223–227 West Jefferson Street in Downtown Louisville (where Jim Mitchell, the “Original Black Panther,” made a name for himself) to Jerry Jarrett’s Memphis Wrestling of the 1970s–90s.

By the 2000s, when the business turned into a veritable monopoly run by World Wrestling Entertainment, OVW (founded in 1993) entered the spotlight as a farm league for the WWE. It developed talent like John Cena (known as the Prototype during his OVW days), Dave Bautista (Leviathan), and Brock Lesnar.

Today, the WWE is out of the picture at OVW. But one of the holdovers from those days, former WWE star Al Snow, has stayed in Louisville and is now the CEO and co-owner of the company. And that is where the action begins with Wrestlers.

The story finds Snow struggling to keep OVW in business. Enter Matt Jones and Craig Greenberg—the Kentucky Sports Radio raconteur and the mayoral candidate, respectively—who want to preserve a “Louisville Icon” in OVW and invest in the venture with Snow. Out of that relationship arises the most interesting, yet least developed, drama in the entire series.

Wrestlers fleshes out the life stories of many in the OVW roster. We witness the transformation of Kentuckian Haley James from problem child to antihero Hollyhood Haley J (Episode 5). We revel in the joy that Louisvillian Mike Walden takes in barnstorming for family and friends at Hillview Softball Field on Crestwood Lane as the babyface Ca$h Flo (Episode 3). We empathize with the struggle of Amanpreet Singh Randhawa (a.k.a. Mahabali Shera) to acculturate to the pro wrestling business in America and keep his integrity as both an athlete and an adherent Sikh (Episode 4). We even catch a glimpse of the inner life of Matt Jones, a self-confessed mama’s boy, as he takes his mom to her first live wrestling match in Harlan, Kentucky, during the Poke Sallet Festival (Episodes 3 and 4).

So, it comes as a surprise when so little of Al Snow himself is revealed in the series. Personally speaking, it would have been fascinating to witness Snow’s transformation from his days as an unabashed “jobber” in WWE in the 1990s—when kayfabe (think of it as pro wrestling’s Holy of Holies) was irrevocably torn asunder by incidents like “the Montreal Screw Job”, and Snow once wrestled his own mascot, a wigged Styrofoam head, and lost—to his role as a pro wrestling elder statesman, the grizzled stoic of Wrestlers.

To be sure, we are made privy to the vicissitudes Snow faces (“the @#$% sandwich” he calls it) in the business. He tries to keep the tradition of “physical storytelling” intact at OVW, while making compromises to Jones and Greenberg, who make constant overtures for better box office and more corporate sponsorships. He navigates the delicate balance of the locker room, where substance abuse and personality conflicts abound and threaten to derail Snow’s “picture puzzle” of a story for OVW. Snow confronts his own legacy as a wrestler and a storyteller. But, the transition—from jobber to sage—is missing.

That said, Snow’s old persona, the leader of the J.O.B. Squad, makes two outside-the-ring appearances in Wrestlers. It is at those moments when Wrestlers goes over from a run-of-the-mill docuseries into something that comes alive. It is those two instances that demonstrate that Wrestlers—to use late 1990s pro wrestling jargon—needs more head.

Brian West

Teaching Artist